Pragmatic Relativism About Belief (Rather Than Truth)

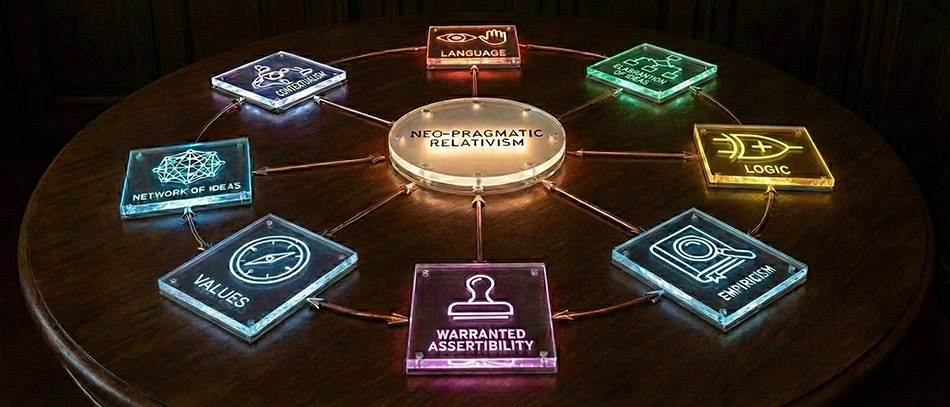

Pragmatic relativists* like me put emphasis on the nature of enquiry, evidence and belief rather than seek to develop a grand explanatory thesis about ‘Truth’. The aim of the diligent relativist is to elaborate beliefs in a way that is consistent with our preexisting ideas. In this context human knowledge can be viewed as a set of well developed and robust beliefs, which have been developed through comprehensive observation or exhaustive inquiry.

We are not in the business of realtivising Truth, despite often repeated claims to the contrary. For me, ‘Truth’ is both a desirable epistemic ideal and a concept that is logically useful. However, I feel that it is more important to understand the reasons why we accept particular ideas either in science or purely personal matters, for example, rather than claim that our beliefs are true in an absolute sense. In addition, understanding our motivations for action in the world is far more significant than constructing grand philosophical narratives.

Relativists are also conscientious fallibilists with a questioning attitude of mind. A central tenet of pragmatic relativism is the axiomatic belief that human reasoning and enquiry are fallible. For the fallibilistic pragmatist, it seems perfectly natural that particular beliefs are accepted in ways that are relative to some wider set of constraints or context. We are, for example, personally constrained by our existence at a particular time the development of human culture, and by our individual life experiences. We pursue particular goals and operate certain practices of inquiry, and are educated within accepted (or fashionable) frameworks of ideas. In other words it is helpful to bear in mind the context in which we lead our lives and substitute new ideas for old.

Relativism involves are more than fallibilism since it involves an empirical, contextually appropriate, pragmatic approach to enquiry and explanation. The epistemic goal of enquiry is arrive at ‘warranted assertability‘ not ‘Truth’. When the relativist is convinced enough by the evidence, or the testimony of others, he or she feels justified in publically asserting an idea as useful, explanatory or predictive. In doing so they also wish to go beyond the simplicity of a binary assessment of either truth or falsity. This stance downplays those binary values (Truth and Falsity) and stresses that our actions in the world are often, made given an incompleteness of evidence within a given context. In addition working hypotheses at the forefront of scientific research can be highly speculative and as such are designed to be testable, rather than be asserted as a robust proposition

Our ability to form relativised beliefs that inform our actions is a fundamentally important evolved characteristic that affects our survival. Beliefs that motivate our ‘decisions to act’ in a research context or in everyday life, represent the most important class of belief. ‘Decisions to act’ might also be fruitful in some circumstances but not in others. especially when change is beyond our control or anticipation. More generally,

Instead of dealing with Truth, pragmatic relativism invokes the arduous process of synthesising observation, enquiry, contemplation and logical consideration into the basis for deciding whether or not a belief is warranted. As previously explained in earlier sections, if we adopt a deflationary view of Truth (see Section 3), our emphasis naturally shifts to a consideration of belief and our standards of evaluation. This philosophical stance values the weight of personal experience, the explanatory power of reasoned ideas, and the coherence of our concepts more than spurious claims to authority.

Due to the very demanding nature of pragmatic relativism we also need to invoke the concept of ‘epistemic entitlement‘ in order to make this outlook practical. In this notion of entitlement we accept that there is a social basis for evaluating ideas that is beyond our personal experience, investigative abilities, educational achievements and intellectual capacities. Epistemic entitlement in this context is merely an acknowledgement that we each have our limitations and so formulate our ideas based to a very great extent on the observations, activities and expertise of others. (See the previous section on Testimonial Truth and Sincerity)

Personal Experience and Beyond

At times our personal experiences provide excellent grounds for belief. If, for example, you were involved in a very bad car crash the evidence of all of your senses might tie together in away that would entitle you to hold an irrefutable belief that the accident actually happened. Indeed it would be nonsensical to believe otherwise. If you gave evidence in a subsequent court case you would be entitled to tell the court the you were involved in the crash and expect the judge or jury to believe you. In such a situation both parties to a case might agree on certain ‘facts of the case’. Given material evidence and the accounts of other witnesses including police and forensic engineers the judge or jury would be entitled to conclude without doubt that a crash had indeed occurred. However coupled to those certainties there might be many aspects of the legal action that could be open to alternative, conflicting and complex interpretations and judgements based on a ‘balance of probabilities’. Was the failure of a car part the result of bad design or manufacturing? Did the car owner ignore a recall notice? Was diver error a contributing factor? Was there conflicting expert evidence? How is the law to be interpreted in a particular set of circumstances? Does previous case law inform the judgment? Could there be grounds for appeal? In the end the attribution of blame and legal culpability might be very complex and be one of interpretation that differs markedly from the brute ‘facts’.

The neo-pragmatist also accepts that supposed scientific ‘facts’ should be seen in the same light. Science, and academic study more generally, creates well supported beliefs developed through enquiry (research) and reinforcement by an interlinked web of mutually supporting (or coherent) ideas. When scientific explanation, for example, is elaborated these well developed beliefs have to be accompanied by speculative conjectures that fuel further enquiry and insights. The trajectory between informed speculation and definite beliefs is for the relativist the result of a process within a context not a consequence of arbitrary epistemic whim.

Personal Significance and Value

It is legitimate to view knowledge or beliefs as varying from the widest possible generalisation to the specifics of communal or personal history. For the pragmatist that does not mean we should value generality over personal experience. The neo-pragmatist, being primarily concerned with the process of investigation and reasoning, can be equally concerned with specific events and wider generalities. For example she can value a judgement in the case of a car crash as importantly as reasons for accepting a particular controversial scientific theory such as the inferred existence of cosmic inflation following the Big Bang. In so doing she will be acknowledge the importance of both ordinary life experiences and grand explanatory theories. How different beliefs are valued of is a matter for the individual and the community of which she is part. For the traffic accident victim with life changing injuries the decision of a court will almost certainly take precedence over beliefs of cosmology. For the post-doctoral cosmology researcher it might matter a great deal how her beliefs about cosmic inflation are treated in a grant application. For the 22nd century historian of science the context of evaluation for the same cosmology will likely be different from that of the theoretical physicist of today.

Common Responses to Relativism

The very mention of the the word ‘relativism’ in various philosophical domains has generated ridiculous and irrational opprobrium! Trite dismissal in a few ill-considered sentences by those who should know better is not unusual. It is my impression that analytic philosophers, do not want to undermine their social and professional status by even whispering the word relativism. I like to find trophy phrases that seek to show a visceral disgust with epistemic and moral relativism, particular the later. My present favourite is “charges of relativism”

The philosophically challenged popular science writer Richard Dawkins appeared to share the indignation of Josef Ratzinger when it comes to relativism in it’s different forms. Cardinal Ratzinger in his diatribes against relativism was no doubt motivated by fallacious claims to authority. No such excuse can be made for Dawkins who said in a 2008 video “Relativism, the quaint notions that there are many truths, all equally deserving of respect, even although they contradict each other, is rife today. It sounds like a respectful gesture to multi-culturalism. Actually it’s a pretentious cop out. There really is something special about scientific evidence. Science works. Aeroplanes fly, magic carpets and broom sticks don’t”. If Dawkins took a more nuanced view, he would realise that research scientists are not in the business of declaring truths. They instead seek to carry out honest, sincere, rigorous and repeatable enquiries and subsequently develop explanations that facilitate predictions. By proceeding in this way, scientist (of all kinds) are deeply imbued with the spirit and motivations of pragmatic relativism.

Sadly some epistemologists who should know much better than Dawkins, perform a couple of quick intellectual sleights of hand and claim epistemic relativism is self-defeating or self-refuting. The first part of the trick is to provide an absolutist definition of relativism. This is is part of the conjurers method of shititing the viewer’s attention from what is actually going on, otherwise known as gaslighting. Part two of the trick is to then use that definition to argue that relativism is self-contradictory or self-refuting. The usual line of attack is to claim that ‘Relativists say all truth is relative. However the relativist makes an exception for relativism. Therefore relativism must be self-contradicting or self-refuting and cannot possibly be true’ …. bla, bla, bla….. you can fill in the rest for yourself. Of course that argument is completely contrary to the spirit of neo-pragmatism and relativism. Relativist almost by definition try to avoid unnecessary Truth claims. Pragmatic relativists are comfortable with uncertainty and instead see it as a stimulus to further enquiry. They are not Truth addicts. Instead, the epistemic relativist, just like the pragmatist , says there does not seem to be value free enquiry or value free explanation following enquiry. How would we ever develop as supposedly ‘objective’ and infallible perspective? How would we know that what we have said of a particular subject is definitively true now and forever? When the epistemic relativist, for the sake of debate, responds to the fortunate ‘holders of truth’ by pointing out the very obvious contextual relativities of the human condition, sleight of hand number two is performed. The absolutist camp says ‘those considerations are trivial … we are discussing the nature of ‘Truth’ and how it is arrived at. Well, good luck with that approach!

I actually sat through an otherwise excellent public lecture on the philosophy of perception where the philosopher went to ridiculous lengths to avoid being labelled as a relativist. This stance was adopted by the lecturer despite the obvious relativities brought about by biological differences in colour perception. The lecturer seemed to have missed the entire point of the relativist stance.

Ignore the Caricatures of Relativism

For the pragmatic relativist the position is different from the caricatures. The relativist is not a ‘truth addict’, but like anyone else enjoys the enticement of what might actually become a lifelong stance. The idealised truth of a belief is just that, a mere idealisation that matters less than the reasons why we consider our views to be justified. Diligent and virtuous relativists about belief ask themselves what explanatory claims, if any, should they provisionally accept? (I specifically do not mean ‘accept as true’. I mean ‘go along with’.) How should I weigh current insights against those of the past? Is it not too much to claim I, and those like me, have finally arrived at some unassailable position that will not be rejected in the future by others with different and perhaps more extensive insights? How can we be sure that a bishop with his ancient texts or the professor with his brand new theory at the forefront of particle physics is telling us the ‘Truth’? For those, like me, who advocate a from of contextual relativism the notion of ‘truth telling’ is often superfluous. That is why I tend towards a position of deflationism about truth (described earlier).

Moral Relativism

The moral relativist insists that we have shared moral values not truths. The relativists says ‘eating human babies is definitely not acceptable behaviour and we all need to agree about that. Those who do not agree will not live amongst us.’ He or she does not proclaim divine revelation on the matter but instead just argues a pragmatic way of trying to prevent such a dreadful situation or a way to deal with the circumstance should it arise.

[* Pragmatic relativism about belief overlaps with the idea of ‘epistemic relativism‘]

Further Reading

Relativism (2004) Maria Baghramian, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-16150-9

A Companion To Relativism (2011) ed. Steven D. Hales, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-1-4051-9021-3

Relativism (2025), by Maria Baghramian and J. Adam Carter in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Version 2.4

Steve Campbell

Glasgow, Scotland

2022, 2026