“… the truth is, it is a misnomer applied

to the pursuit of those who are devoured by a desire to find things out….” C.S. Peirce.

3.1 A Quick Overview of Explanatory Theories of Truth and Reasons Why They Might be Unnecessary

Theories of Truth

In a previous section, I stated that there can be no general theory that can tell us whether or not an individual description or explanation is truthful, in the sense of being accurate. Nevertheless, there have been many attempts over a very long period to provide more general explanations of ‘Truth’, including the minimalist view that there really is not a lot to explain.

For some pragmatists explaining the concept of truth might be seen as a waste of time because the focus of pragmatism is on examining the justification and utility beliefs that we all hold. I do not agree because I consider ‘truth’ to be an important and useful epistemic idealisation that informs our pragmatic goal of formulating useful explanations following enquiry.

Explanatory Theories of Truth are often taken to be alternatives to one another, which is rather unfortunate. For me, it is better to ask whether or not these explanations are complementary in some way and so can be taken together to form a more meaningful, more integrated and more comprehensive view. If you want to think of that as a hybrid theory so be it. In what follows, I argue that we can develop a perspective that can be informed by more than one set of considerations and that often they need not be mutually exclusive or inconsistent.

For example, you might adopt the metaphysical stance that your thought-based interpretations of the world can be thought of as exhibiting some form of correspondence relationship to what is happening outside of your head. From the pragmatic perspective it seems utterly pointless to develop a vocabulary that makes reference to objects in the world and then adopt an idealist perspective that only the mental ‘exists’. Such scepticism about physical objects would need some from of justification, which for the pragmatist cannot be found in experience. For example, the signifier ‘tree’ points to something in the world that exists. By using the word tree to signify or describe an object we are not revealing the ‘thing in itself‘, in all of its biological splendor. We are simply making reference to a member of a particular set of large woody plants that we have classified in an arbitrary way as a matter of communicative efficiency. Although the classification of particular plants as ‘trees’ is a human construct, the pragmatist assumes that that our use of the signifier indicates a correspondence to objects within the world. For the pragmatist, to believe otherwise about observable objects would be extremely foolish. However the use of nominal terms does not capture the entirety of our understanding in the matter of trees or anything else.

It would also seem to help our understanding if our ideas inductively and deductively cohere together. If, in addition, even our more abstract ideas are useful in some practical or intellectual sense, so much the better. At the same time, you might also adopt a particular semantic (linguistic) explanation of the truthfulness of particular assertions. These theoretical features of an idealised or abstract concept of truth need not be mutually exclusive. Indeed it would seem intuitively obvious that for the purposes of reasoning and understanding that all of the characteristics mentioned so far might be regarded as desirable.

Whilst acknowledging these possibilities, some might simultaneously hold the view that the label ‘true’ that we can attach to a statement does not itself confer additional meaning to a statement. The proposition that ‘something is the case‘ might legitimately seem identical to an assertion that ‘(it is true that) something is the case’. From a semantic perspective, the use of the word ‘true’ might also be a rhetorical device providing emphasis or an affirmation of agreement.

Our view will to some extent be determined by whether or not we wish to place linguistic (semantic) and logical emphases on our understanding or develop a more pragmatic or empirically epistemic approach. It also depends on what type of logic we also wish to apply. Epistemic logics, for example, deal directly with the concept of belief.

It sometimes seems to me that those expounding particular views about the nature of truth are resistant to the notion of synthesis and often seek to emphasise what they regard as flaws in the views of others rather than deliberately seek ways to integrate the novelty of their personal perspective within a wider and richer narrative. Discarding ideas is a long-established practice in Western thinking. Sadly I see little prospect in this situation changing, perhaps because developing an integrative approach is more intellectually demanding. Nevertheless, there are philosophers who now recognise that explanatory theories of truth (and related concepts such as meaning) are best viewed as mutually supportive.

There now follows a very brief introduction to the scope of theories of truth, in which I ask you to determine for yourself whether or not the theories introduced below contradict or are complementary and compatible with each other. I assert that if you find the concept of truth useful, we can have a richer and more expansive view if one can simultaneously hold different explanations of truth and find a way to integrate them.

a) Metaphysical Correspondence Theories

‘The cat sat on the mat‘ is used in epistemic accounts, written in English, as a prototype expression to assert that there is a relationship between our very limited sensory perceptions, our linguistic assertions and the external world. We tend to take it for granted that the cat sitting on the mat is observable, comprehensible, is a state of affairs in a real world, and can be meaningfully expressed in a natural language, such as English. The pragmatist sees no value in radical scepticism about the possibility of such states of affairs, since sceptical ideas also need justification.

‘The cat sat on the mat’, ironically created by GAI. Despite obvious flaws this synthetic image does represent another type of pragmatically useful communications ‘token’. [Cats do not have round pupils. The texture of the floorboards is obviously wrong in front of the mat. I have never seen a shiny mat that seems to indicate the notion of a hard or gloss painted surface.]

In order to make philosophical sense of this prototype sentence most of us agree on the metaphysical or ontological necessity that a world exists outside of our heads. We have access to that world through our senses, although perhaps in an arbitrary fashion created by biological evolution of our species. [The general reason we have perceptions, at least in biological terms, is to maximise our survival and reproductive fitness. However it is now clear from the empirical evidence that our optical perceptions, for example, are definitely not like the result produced by an engineered brightness measuring device, such as a digital camera.]

Nevertheless, we can ask how can human thoughts correspond to states of affairs in the external world. Or more simply, what is the nature of the apparent correspondence relationship? If I say to you “please paint the brown door pink” and I come back a day later and see that the same door is now pink in colour we clearly have a similar understanding of the terms brown, pink, paint and door. For both of us there is a correspondence of meaning of terms with regard to action within the world, and our communications in the matter of painting doors. More generally, for the pragmatist, the functioning of society, and the meanings it creates (as understood by a Theory of Communicative Action) displaces the importance of philosophical speculations about truth and instead enriches our understanding of the social context of agreement.

In epistemic terms, correspondence can be envisaged as a form of representational ‘mapping‘, albeit one that is dynamic and might change over time, especially with respect to abstract concepts. (‘Mapping’ is used here in the normal mathematical sense). Nevertheless, our perceptions are so limited that it is difficult to imagine there is any strict isomorphism (or “structure-preserving mapping”). In other words our perceptions and assertions do not take into account the full complexity of any physical object. Words and symbols are mere tokens of objects and less rich than our reflective observations, which are in turn very limited with respect to the totality of the object.

There are many legitimate debates about the way our sensory apparatus works and our ability to develop perceptual experiences that map onto the world. When we also take into consideration the central idea of biology that ‘life evolves’ and is shaped by the environment through genetic mutation, heritability and natural selection, our view of correspondence takes on additional complexity.

In the context of evolution, it is tempting to treat our ‘internal’ neurological states as an arbitrary biological process designed to produce an adaptive behavioural output given an accumulation of sensory inputs. Perhaps that is a pragmatic way to look at correspondence, however our internal mental life has the feeling of being much richer!

There are also said to be non-metaphysical epistemic versions of correspondence theory including a version that is based on the philosophical description of ‘facts‘. However, I am ill at ease that merely invoking ‘facts’ as the substantive basis of what can be said in epistemology. On the contrary, it is the job of epistemology to explain why we can claim to ‘know’ certain ‘facts’, not to begin by assuming their existence.

b) Pragmatism Should Not Be Seen As A Theory of Truth

For me Pragmatism should be seen primarily as a philosophical stance that includes ideas about belief rather than an epistemic theory of truth. The american neo-pragmatist philosopher Richard Rorty also had similar views that have been dubiously characterised as anti-epistemological. In a short video available on YouTube, he says:

“I think it was unfortunate that pragmatism became thought of as a theory of Truth. I think it would have been better if the pragmatists had said, ‘we can tell you about justification, but we can’t tell you about truth’. There is nothing to be said about it. And as we know how we justify beliefs, we know that the adjective ‘true’ is the word we apply to the beliefs that we have justified. We know that a belief can be true without being justified. That is about all we know about truth. Justification is relative to an audience and to a range of truth candidates. Truth is not relative to anything. Just because it isn’t relative to anything, there is nothing to be said about it. ‘Truth with a capital T is, sort of like, God. There is nothing much you can say about God. That is why theologians talk about ineffability Contemporary pragmatists tend to say the word is indefinable, but none the worse for that.. We know how to use it. We do not have to define it.”

[Also see my YouTube video playlist Rorty Speaking.]

The classical American pragmatists were nevertheless engaged in discussions about truth, probably due to the philosophical fashions and the social authority of religion at that time. In 1907 William James wrote “True ideas are those that we can validate, corroborate and verify. False ideas are those that we can not.” (His italics). By contrast in his 1938 large book ‘Logic: The Theory of Inquiry’, John Dewey, when he was in his late 70’s, rather amusingly made only one reference to truth in the index (p 546) and that was to a redirection.

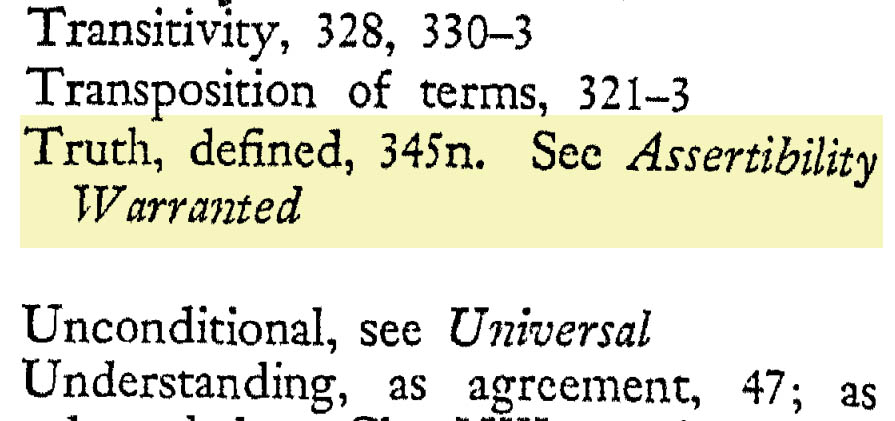

By this stage in his long life Dewey really sees little point in distracting the pragmatist from more important considerations by becoming embroiled in debates about Truth. Indeed he says (in Logic The Theory of Enquiry, p 345) “The conditional status of scientific conclusions (conditional in the sense of subjection to revision in further inquiry) is sometimes used by critics to disparage scientific “truths” in comparison with those which are alleged to be eternal and immutable. In fact, it is a necessary condition of continuous advance in apprehension and in understanding” In other words even scientific enquiry does not produce truth. He the makes references to C.S. Peirce in the footnote:

By contrast the modern neo-pragmatist might assert that our views should be good enough to be useful or exploitable or have consequences in an explanatory or practical sense. We simply need not make reference to truth, except in the sense of an epistemic idealisation that is taken as the (probably) unachievable goal of inquiry.

For the sake of completeness let us temporarily accept in an ironic or counterfactual way that an idealised form of pragmatic truth would be the collection of views that we might develop after very extensive, or even “endless”, investigation, in which we have ruled out less favourable but obvious alternative ideas. More simply, truth for all practical purposes, might represent the current limits of human enquiry and ingenuity of explanation. From the neo-pragmatist perspective, warranted assertibility or social acceptability amongst one’s peer group is the highest aspiration we can legitimately have for a proposition. Pragmatism, almost by definition, does not hanker after absolute certainty of belief or any idealised truth status. The addiction to truth claims into which we have been educated into is hard to relinquish. However it seems logically unsatisfactory to even attempt to define truth in pragmatic terms as being related to the inferential outcome of a particular set of enquiries.

Of course, a pragmatic approach does not rule out the possibility of a correspondence of our ideas with what exists in the world since it is not a stance that is explicitly metaphysically based*. In any highly idealised view of truth, ideas could be expressed in a way that bears some kind of token correspondence with the world, and also be useful by a chosen criterion or criteria, and also have some practical or explanatory value, without involving any contradiction.

*All theories of any kind, of course, have metaphysical or ontological presuppositions.

[Discussion of pragmatism continues in section 4 and section 5.}

c) Coherence Theories of Truth and Justification

In Coherence Theories, reliance is placed on the interrelatedness and mutual support of ideas rather than individual propositions or foundational beliefs. I subscribe to the view that coherence is a desirable feature of justification. I have no explicit reason for thinking that coherence acts as a sole and definitive explanation of truth. Others have pointed out that, although internal coherence within a framework might be high, that would not necessarily make it truth bearing in an idealised sense. A set of political or religious ideas could be internally coherent, given a set of descriptive axioms, without them being regarded as either true or useful.

The pragmatist asserts that individual sentences only make sense in the context of using a descriptive language and within the limits of our perceptions and actions. Nevertheless, all belief systems have basic axioms which we often take for granted or remain unarticulated (as discussed previously).

In any complex domain of belief such as in the sciences, there is a very heavy justificatory reliance of the inter-relatedness or coherence of ideas. For example, the theories about the physical evolution of the world and biological evolution of species are supported by a vast number of observations, explanatory theories and the interconnectedness of every branch of science.

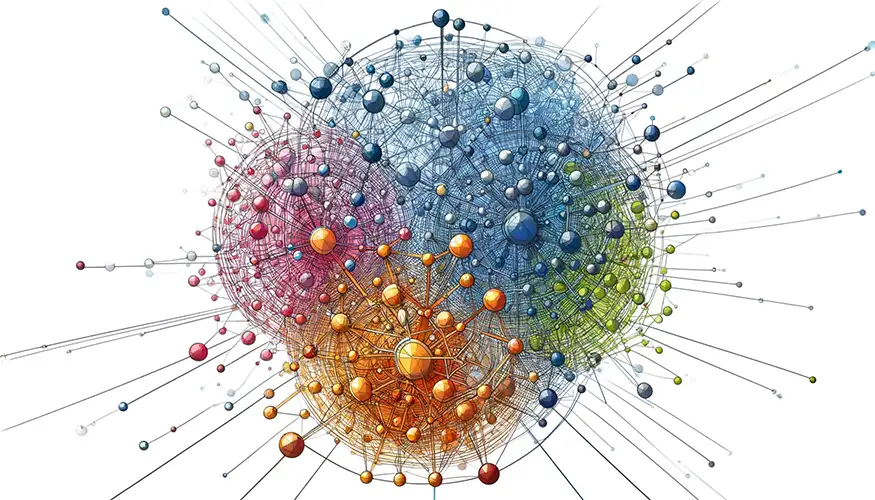

In learning about the world, we rely very heavily on the process of induction and logical deduction to develop explanations. If we could extend that analysis over the totality of all statements that we accept we would have an ideally coherent set or network of beliefs, provided that none were contradictory. In that idealised circumstance, the coherence theorist might declare that the justification (or truth) of our entire set of beliefs rests on the interrelatedness of our ideas to one another.

Strong forms of relatedness espoused by coherence theorists are primarily achieved by the use of logical connection between ideas. Logical connectives, soundly applied, bring together assertions into compound statements that preserve the warrant (acceptability or truth) of the starting assertions (as described in the section on logic). For the Deweyian pragmatist acceptance or warranted assertibility is stressed as the desirable criterion rather than truth. The more global view is that the interconnection of all warranted ideas that we formulate results in the formation of a logically defined network that is truth-bearing for some epistemic theorists or defines global utility for the pragmatist.

However, it seems a ridiculously restrictive requirement that all ideas need to fit into one coherent whole. We could instead have distinct domains of thought or explanations at different levels of generality. An error in one domain need not impinge on the correctness or assertibility of another. A logical contradiction in quantum mechanics need not have any implication for our understanding of reproductive behaviour in chimpanzees, for example.

d) Deflationary Linguistic (i.e. Semantic) Theories

Deflationary theories posit that the predicate ‘is true’ adds nothing to the meaning of a sentence in which it might be found and is therefore entirely compatible with a pragmatic stance. After one asserts that something ‘is’ or ‘is not’, the word ‘truth’ becomes superfluous. These theories hold that ‘truth’ is neither a thing nor is it a substantive property of a statement. In some forms of deflationary theory, the truth predicate is seen merely as an instrument of reference within sentences.

The semantically recognised exception is when we refer to a collective of statements such as ‘Everything she said is true.’ The sentences ‘Everything she said’, ‘What she said’ are obviously incomplete and therefore do not make sense as we lack a predicate. So there appears to be an expressive need for the word ‘true’ in such cases, if the purpose of a sentence is to communicate the testimonial sincerity of descriptively accurate ideas.

The insistence that the concept of ‘truth’, and its negation ‘falsity’, are only linguistic devices seems to jar with our everyday experience. If we have a theory of meaning that is fulfilled by the existence of real or abstract objects, and properties or events, the scope of deflationary theory seems to have limited appeal. That, of course, does not mean we should ignore the relevance of deflationism when applied to explanatory theories of language and meaning.

If we are neo-pragmatists the appeal of deflationism about truth is already less of a concern, since our goal is to formulate a set of criteria for acceptance of particular ideas or beliefs. Pragmatists like me neither seek an absolute basis for our beliefs on individual matters nor produce absolutely definitive theoretical basis for truth. Theorising about ‘Truth’ might be of course be personally interesting for the philosophically disposed.

f) Primitivism

Another alternative perspective is to consider ‘truth’ or ‘is true’ to be primitive concepts that have a fundamental epistemic value in their own right. For primitivists, the predicate ‘is true’ is taken as a substantive property of a statement, although not of the ‘thing in itself’, which is the subject of this type of reference.

If the primitivist view is correct, when we use the predicate ‘is true’, it would then be a bit like saying, ‘The cover of a snooker table ‘is green’. No further explanation of green is required for the sentence to make sense or hold meaning to a person of normal colour vision who understands the meaning and appropriate use of the word for that colour.

Green is a term used to describe a perception or a property of a thing. However, the predicate ‘Is true’ can only apply to assertive statements, not the things to which they refer. The notion that the ‘is true’ predicate has an equivalent epistemic basis, which is analogous to our accounts of perception, still has a few defenders.

One very obvious advantage of primitivism is that it helps to provide a justification for our beliefs.

If ‘truth’ and ‘falsity’ are indeed epistemically primitive they need to have, almost by definition, a linked status that is axiomatic.

g) Foundationalism About Truth

No matter how hard we try to eliminate static foundations for our beliefs, it seems that there are certain very basic assumptions we make when we construct ideas or look for inter-relationships between them. The axioms of our belief systems (explained in previous sections) are the most fundamental assumptions that we make about all of our ideas. Although they are often very abstract and sometimes not even explicitly stated, we place reliance on them. I argued that, from a network theory perspective, these fundamental assumptions are no more than highly connected nodes within a coherent network.

If you wish to preserve the idea of foundations for belief, I invite you to consider them to be an emergent property of a coherent system of ideas. (Please see the section on epistemic emergence).

h) Pluralist Theories

Pluralism, in this context, means that the concept of ‘truth’ has different uses, properties, meanings or implications in different domains of discourse. Simply put, there are different ways for statements to be true. For example, the truth or falsity of the sentence, ‘The cat sat on the mat’ has a different use, meaning or implication from the way that ‘truth’ is used in logic when defining the nature of the logical connectives by the construction of ‘truth tables’ (referred to in section 2.5.4). If very different conditions have to be fulfilled to hold that propositions from different domains of thought are taken as true, it seems pragmatically useful to at least consider the possibility of pluralism.

Pluralist theories have been developed in the 21st century. However, once the floodgates are opened and more than one type of truth is admitted the whole subject can be overwhelmed with a fairly unproductive analysis of types and categories and the logical basis for combining truth types. The answer of the pragmatist is simple; only be concerned with the reasons for a particular justification and don’t worry about the existence of types of truth.

Producing a Synthesis of Ideas

Susan Haak is an example of a philosopher who has tied together the explanatory concepts of foundationalism and coherentism into to an idea she referend to as Foundherentism. From my perspective this is merely the beginnings of a sensible synthesis that will lets us better understand the nature of knowledge and truth if such can be formulated.

Further Reading

The Nature of Truth Classic and Contemporary Perspective, MIT Press. ed. Lynch, M (2001)

https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/nature-truth

Evidence and Inquiry: Towards Reconstruction in Epistemology by Susan Haack

Publisher Page

Online Articles

Truth

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/truth/

https://www.iep.utm.edu/truth/

Correspondence Theory

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/truth-correspondence/

The Pragmatic Theory of Truth

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/truth-pragmatic/

An excellent article given the proviso that even two of the classical pragmatists don’t see truth as more than an idealised abstraction.

Coherence Theory

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coherence_theory_of_truth

Pluralist Theories of Truth

https://www.iep.utm.edu/plur-tru/

Primitivist Theory of Truth

Tarski and Primitivism About Truth by Jamin Asay

Book preface on Semantic Scholar by Jamin Asay

Version 2.8.1

Steve Campbell

Glasgow, Scotland

2020-25

< previous | Index | next >