4.4 Mill’s Methods: Logical arguments taking us from repeated observations to causal explanations

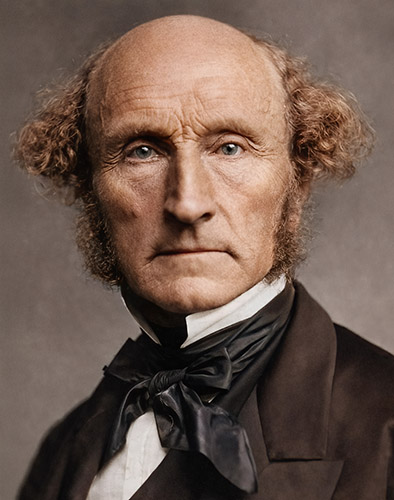

In the 19th century, the English philosopher JS Mill provided some algorithms or rules of thumb that show us how to take a set of repeated observations and infer causes. I include them here, because for me they are an early masterpiece pragmatic thought that has great influence today. I suspect William James believed the same when he said in the dedication to his 1907 book Pragmatism “To the Memory of John Stuart Mill from whom I first learned the pragmatic openness of mind and whom my fancy likes to picture as our leader were he alive to-day”

“Mill’s Methods” are well suited to the practice of medical research, for example and so make important reading for the pragmatist since they are concerned with practical reasoning.

If we go to chapter 8 of the free 8th edition of ‘A System of Logic’ Mill suggests forms of argument (or methods of analysis) that might be called inductive, in the sense that they are derived from collections of observations. These ideas have become popularly known as Mill’s Methods.

These methods are:

1) The Method of Agreement which operates “by comparing together different instances in which the phenomenon occurs”. Mill says “this method proceeds by comparing different instances to ascertain in what they agree”

To apply the Method of Agreement in medical research we might look for a factor that might be a cause of a disease. In other words, if epidemiologist wishes to discover what risk factors lead to a particular disease they might look for a factor that is common to people suffering from that condition. Respiratory exposure to asbestos fibres in workers dealing with this substance has been found to be a common factor in the rare form of lung cancer known as mesothelioma. Indeed it is thought that mesotheliomas of the lung are almost always caused by asbestos fibres being taken into that organ. Here we have an almost perfect example of the Method of Agreement. In statistical terms, it’s similar to noting a high correlation between a certain factor and the occurrence of an outcome across many different contexts or samples.

2) The Method of Difference arrived at “by comparing instances in which the phenomenon does occur, with instances in other respects similar in which it does not”. “This method compares an instance of its occurrence with an instance of its non-occurrence, to discover in what they differ”

The ‘Method of Difference’ does the exact opposite of The Methods of Agreement and seeks to determine a cause by looking for something that has distinguished particular instances (or people). So if a medical condition (or a healthy trait) was found in certain members of the population but not others we might seek not to find out what is common to the affected group but what is different in those unaffected in the wider population. Of course, in practice, we might conjoin the methods of difference and agreement, particularly when looking for multiple risk factors in conditions such as heart disease or bowel cancer. In observational studies, it is equivalent using a regression analysis or stratification of sample groups to control for confounding variables. In experimental work a controlled difference is introduced and other relevant parameters are kept the same.

Mill says of Methods 1) and 2) “Both are methods of elimination”. “The Method of Agreement stands on the ground that whatever can be eliminated, is not connected with the phenomenon by any law. The Method of Difference has for its foundation, that whatever can not be eliminated, is connected with the phenomenon by a law. He also compares this with the deductive process of elimination in dealing with mathematical equations.

3) The Joint method of Agreement and Difference

This method helps strengthen causal inference by demonstrating both the presence of a factor when the outcome occurs and the absence when the outcome does not occur. In clinical research this method would be encountered in a randomised placebo controlled crossover study in which firstly a participant randomly receives either the treatment of the placebo. The participants in the trial are then ‘crossed over’ to the opposite intervention.

4) The Method of Residue “Subducting from any given phenomenon all the portions which, by virtue of preceding inductions, can be assigned to known causes, the remainder will be the effect of the antecedents which had been overlooked, or of which the effect was as yet an unknown quantity”. In other words when we exclude known or at least accepted causes for particular effects what are we left with by way of explanation? This is also very clearly a forerunner of the idea of a statistical model.

This method is comparable to residual analysis in regression modelling in modern statistics. What remains unexplained by the known factors might be attributed to other variables not included in the statistical model. It’s a way of identifying potential missing causal effects that could be influencing the outcome of a treatment.

5) The Method of Concomitant Variations looks at the magnitude of proposed effects and causes. This would apply “in the cases in which the Method of Difference, strictly so called, is impossible”. In other words, the difference is not complete but instead varies in quantity. “The quantity (my italics) or the different relations of the effect follow those of the cause”.

In the Method of Concomitant Variation, we are looking for what we now think of as a statistically deduced correlation between the magnitude of the effect and the proposed cause. The dose-response relationship in pharmacology is perhaps an obvious example. Give patients a greater dose of a drug such as paracetamol (Tylenol) and they will experience more pain relief or a longer pain-free period. Mill uses the example of friction and says that we can only experimentally reduce frictional effects in slowing down moving bodies we cannot remove them entirely. He also warns that we should not extrapolate outwith the range of the observed limits, which is in effect bringing in another logical constraint. In statistical language, this method investigates the strength and direction of the association between variables, adjusting for other factors in multivariable regression.

Of course, Mill was well aware that the potential causes we ascribe might not be the only ones we could find or the only which might apply exclusively. In other words, there might be additional relevant processes (or variable) or that our our explanation may have only identified a partial cause or contributing factor.

Notice also we have a starting premise, or a “canon” as Mill calls it. In the Method of Agreement, the premise is “If two or more instances of the phenomenon under investigation have only one circumstance in common, the circumstance in which alone all the instances agree, is the cause (or effect) of the given phenomenon”. We now see that this kind of inductive inference also needs a starting premise, which in itself we might label as having a ‘logical’ quality. Deduction and Induction then begin to appear as if they have underlying characteristics in common; argumentative premises. Mill himself says “the Method of Residues, as we have seen, is not independent of deduction”.

Nowhere in these ideas above need we be over-concerned with absolute truth or certainty of belief in our conclusions since we are not applying some form of highly restricted classical logic. Nevertheless, we are adopting what might be referred to as a rational and pragmatic approach in order to produce testable ideas of practical value.

Version 3

Steve Campbell

Glasgow, Scotland

2017, 2019, 2024, 2026